Wait! Spoiler alert! Do not read this essay until you've seen the film!

What’s Water Time About?

An Essay on Critical Thinking

You’ve seen my film, right? Maybe you loved it, maybe you hated it. But for some reason you wanted to hear what I have to say to someone who’s viewed it. So you came here. Let’s see how it goes.

A common question a filmmaker (or any storyteller) might get is this: ‘What’s it about?’

In the case of Water Time (Part One), there are several answers, albeit in the form of more questions, such as ‘Who killed JFK?’ or ‘Why did my friend have to die in Vietnam?’ or ‘Why don’t people listen?’

Or possibly the literal question that launches the story: ‘Is there something wrong with the filmmaker (me), or is it the world itself?’

Although I tried to leave some wriggle room, the answer to this last one – in terms of my intent – is that it’s the world itself that has the problem. By this I of course mean my fellow humans. In general. Not necessarily you personally. (That I ‘have problems’ is inarguable, but that’s a separate subject.)

How did Jon Rappoport put it in his kindly movie review?

‘…he confronts lawyers and ex-pats and dropouts and people on the side of the road with this evidence and he records their reactions extensively, and we finally see what the resistance is all about… I'm talking about how people resist the truth, in their own words, through their own confessions, live, in front of the camera. This is truth on a whole other level…’

Resistance? What Jon is referring to, I believe, is an inability to think critically.

Critical thinking. The resistance thereto…

That’s what the damn story is really about. Yes, there are subplots – like the issue of my best friend’s death, the bit of respite I would get from wave riding, what travel in Mexico is like, etc. -- but that’s the crux.

It’s for good reason that I use and then re-use this quote from A. Conan Doyle, via his fictional character Sherlock Holmes (spoken to Doctor Watson): ‘Once you have eliminated the impossible, whatever is left, however improbable (emphasis in the original), must be the truth.’

True true true! If you don’t understand that there is profound truth somewhere in Doyle’s aphorism, then it surely will not work out between us: you might as well move on forthwith. Now. Bye!

But why do I qualify by saying there is wisdom somewhere? The problem, the reason for the qualifier, lies in defining what is impossible. If you can’t do that properly, there is little practical wisdom in Conan Doyle’s words. Yes, the devil is in the details!

Let’s get specific. Always best.

In the film, in my quest to uncover the identity of the killer of the 35th president of the United States (JFK) and thereby understand why my childhood friend had to die in a far off, illegal, immoral war, rather than be surfing with me, I go to great lengths to demonstrate that there was a fist-sized exit wound in the back of JFK’s head, and which likely resulted in his death.

If you don’t accept that I proved this, I would ask you… beseech you… to go back and watch that part of the film again. In fact, for your convenience, I’ll put a couple minutes here to remind you. If you watch this, please pay attention, because I’m going to define impossible based on the evidence in the film and/or here…

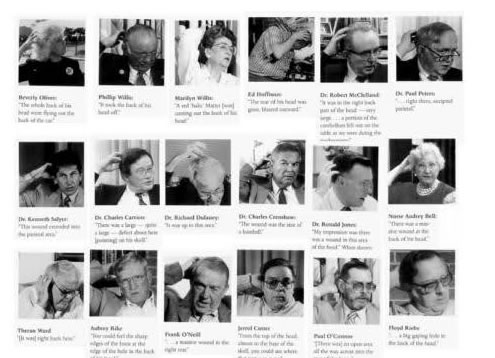

Here’s the drawing from one of the Parkland doctors, a rendering of what 31 witnesses saw (a frame grab from the film), based on their own words.

Now let’s look at the official autopsy photograph, which the Warren Commission used to ‘debunk’ all the witnesses to the exit wound. This is really important! We get this right, we can forget about all the bullshit we’ve heard about the assassination, how ‘we’ll never really know the truth,’ how bad (or good) a marksman Oswald was, how and why he was fluent in Russian at age 21, why he was calmly drinking a coke 90 seconds after the assassination, the fact that the rifle they first found was actually a German Mauser, and so forth and so on.

Here is one definition – what scientists refer to as an operational definition – of ‘impossible’: It is impossible that both of these images represent the reality of the back of JFK’s head on the afternoon of November 22, 1963.

Agreed? Good. Now, what’s more likely:

That all of these 18 people (including doctors, nurses, physician assistants, an FBI agent, a Secret Service Agent), plus about a dozen more (a total of 31), are either lying or delusional about what they saw… or that the photo is faked?

Is one possibility more likely than the other?

Notice that they are all pointing to the location of the exit wound.

Upon this question hangs a lot more than my own sanity, so please think carefully. In fact, on a certain very real level, upon this question may hang the fate of humanity. I kid you not. Speaking of hanging: hang in with me here!

Listen: According to a peer-reviewed study of eyewitness reliability, the accuracy of detail recollection rises exponentially with the number of witnesses who agree upon it. To sum up: If thirty-one witnesses agree on a detail, the odds that it is inaccurate becomes infinitesimally small. In other words, practically speaking, it is statistically impossible that all these people are incorrect in their recollection of the head wound.*(footnote)

The photograph is a fabrication. Okay? (That the autopsy x-ray has also been proved to be a fake can be taken into account, although it’s not strictly necessary.) Let’s get on with it, shall we? What’s my critical thinking point here?

That the autopsy x-ray is also fabricated is inarguable.

(Google ‘JFK x-ray + fake + Mantik’)

Has to do with the other linchpin of critical thinking, aside from defining impossibilities in order to ferret out ‘a truth’ (the above autopsy photo is a fake).

Can you guess what that linchpin is?

It’s one word…

I’ll give you a minute…

It has twelve letters…

Starts with ‘i’…

(footnote)*I read the study some months ago but cannot find it again. (Anyone who comes across it please email me at allan@banditobooks.com.) The study had groups of subjects watch a short action film (under four minutes I recall) then were asked to describe details. If a single subject described something, the accuracy was as expected, i.e., not great, maybe 50%. (I’m hazy on the exact numbers.) But when two people described the same detail, accuracy went up to over 90%. With three, it shot up to over 99%. By the time they got to a half dozen or so, it was ridiculous, like 99.99% accuracy. A number like thirty-one would put it in the billions-to-one that an inaccuracy was described (this is how exponential math works). You really think about this, you understand the importance in the matter of the exit wound.